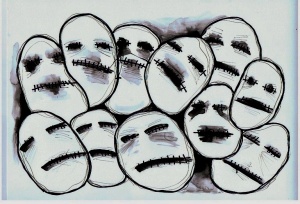

Artwork by Jane Burn

Edited by Louise Larchbourne

All the gardens

The poet sat in the garden that had taken fifteen years to

make. Fifteen years was about right. Before that a garden

wasn’t ready, after that it became blowsy and overripe, like

a single flower. She looked back to the other garden, no doubt

way past its best if she could even reach it, but it was the garden

of its time. She did not think of herself as a poet then. She did

not think it was given to women to use words on behalf of others.

She left that garden and gradually, in many different actions,

created this one. And here it was. Its alignment was not so very

different from the other one, and she remembered weather like

this, days like this, birds with the same song. But it was moving

on. No garden is finished. Nothing stays still.

By Sally Evans

THE DEAD TIDE

How long have I been here caught between the tides?

I breathe in oxygen,

yet my heels are shackled with a blacksmith’s silver chain,

hooked to a swaying seabed.

At night I heard the whispers of Mermaids,

the chattering of the seafaring dead,

where beneath me a new world exists;

a world that I can hear only like a rustic pin

drifting on the surface of a vast ocean.

I’m the dead tide,

I’m silenced,

the lost and the disappeared.

By Matt Duggan

Be Still Now (For J.D.)

Be still now, the parting is over,

the rain and mist descend on northern hills,

the autumn sky is darker than before, time’s movement

ceased. The coaly Tyne remains awake, listening

for its songs, one bonny voice now cast adrift

upon the tide and carried by, unmoored but safe,

at peace now.

Rest now, lass. The hard road lies behind you.

Slip away with the old river, through far, green

acres, byres and sheep folds, the wild geese

overhead and slow smoke rising from steadfast

moorland cottages. The days must bide their hours

without this songbird soaring clear above the sun.

Be still and rest now.

By Lesley Quayle

Ces mains

These hands,

often struck

with yardstick,

hair brush,

or any other

weapon of war,

ces mains

learned that they

were best kept

out of the way,

out of danger.

These hands

learned that

other hands needed

holding –

frail hands,

confused hands,

these hands,

eagerly reaching out

to those in want

or need,

finding hands to hold

or guide,

these hands,

never raised in

anger,

these hands,

gentle,

kind –

ces mains

are

my hands

By Léa Forslund

First Signs

Two cock pheasants are fighting, wings flattened

like the halves of a severed butterfly.

I see the panic of separation

in the brutality of clashing beaks.

The fizzing brown river feels it, too, tries

to reel in its spate with white fingertips,

unable to fathom its fright, folding,

folding itself into a confusion.

Even the swallows’ manic scissors don’t

slice soft air for joy, but for survival.

My barren body gave birth to this Spring.

I’ve pulled it from the freshness of my wounds,

left it to weep on the fell. It glistens

like a solemn promise, a consequence.

By Catherine Ayres

Devilled

Waiting for connecting flights,

I watch TV. In Baghdad a young soldier fires,

fells an Iraqi, yells triumphant, “Got ‘im!”

The fallen man attempts to rise. The boy

fires off another round. The body twitches,

shimmers, stills. “Got the bastard!”

my compatriot shouts in glee.

“It’s just like shooting squirrels back home.”

I turn away and realise Death is sitting next to me

in the plastic airport lounge. With a sideways flick of eyes,

I thought I’d summed him up:

thinning fair hair, corporate permatan

pastel shirt, diamond solitaire

probably from Texas.

To ward off conversation, I’d pulled out

a book and lost myself in alibis.

As we prepare to board, he tells me

that he’s a Platinum Flyer. “Oh really?” I reply,

in tones designed to cut off overtures. “Yes,” he says,

“I’ve flown more than a million miles but then

there’s always folks who’re eager

to buy guns.” It’s then I see the skull

that glows beneath his skin,

the pointed teeth.

By Susan Castillo

That Day

They kept us in the classroom until a masked man

rang a bell, then they took us into the yard, lined us up

along one wall and some of us wet ourselves, I was one.

Seventy years have passed, but I remember that too clearly,

the hot trickle turning icy cold, the chafing. We stood there

for hours, my knees kept locking, I tried to keep moving

but only slightly, the thought of drawing attention,

of masked men seeing the wet patch on my trousers

frightened me more than anything else that day.

We all heard explosions, saw clouds of yellow and purple

rising up, dirty and stinking, and I thought back to earlier,

a silent bare morning, of how I’d thought of pretending

a fever in order to stay at home, how I’d wanted

to make sure my mother was not going to kill herself

today, how she looked so sad when she thought I wasn’t

watching her, how she burnt the toast, and I told her

it didn’t matter, how I forced myself to eat it, to not mind

the scrape of rancid butter, the memory of marmalade.

Then shouting, closer, a barrage of shooting, and we,

just twelve years old, a line of us up against the wall,

the masked men waiting, then Peter went berserk,

he lunged forward out of the line, and one of the men

cracked his skull with his rifle butt, Peter crumpled,

I thought of his story he’d read last week about his sister’s

hamster, how funny it had been, I thought of how his

shirt tails always came out of his trousers, how he managed

to get ink on his knees. He lay in the school yard, broken.

By Catherine Edmunds

Gorge du Loup

Cloud shadows, sunlit hamlets

and the curve of a damaged viaduct –

from this high view point my eye

follows its form, from intact line

to the bombed remains –

impossible to think of war here

now, as all around, in the tangible

depth of air there are swifts

flicking, flitting, back and forth

in their element. They shriek

and swirl. For a moment

I feel my centre clench;

I am filled with the urge

to launch out

over the parapet

to soar with them,

wide open, screaming.

By Sarah J Bryson

house of correction

behind the sharp sharp white fence,

praetorian guard of hypocritical zinnias

the house stood, a deadly phalanx

she, the general, was its shadowless

unbending mind inside behind

the frowning veranda where i parked the bicycle

borrowed from next door

if you opened the french doors, frogs got in at night

and in the daytime, jehovah’s witnesses

if you were lucky, when you were sick in bed alone

but even with the french windows open, you couldn’t get out

cemetery field of crucifixes, the lattice

is too powerful a pentacle

she was the house

spirit of the lattice

let me out

let me out into the sunlight

grant me its

amnesty

By Mandy Macdonald

An earlier version of this poem, entitled ‘exterminating angel’, was published in Poetry Scotland, Winter 2013–14

Life cycle of a hyacinth

Starts slowly, roots

a cautious wormery,

spire of fingernails praying

green in the dark.

No one notices.

Pushes her head through

hands, stands primly

in her own limelight, robust

echo of ultraviolet curls.

Throbs with filthy secrets, smears

thick whispers on kitchen walls.

Gouges the sky with nodding

cotton bud, blows a glass

cathedral bleeding handspans of blue.

Aches at the window, heavy

with absence, a singed

lamb’s head full of lies.

By Catherine Ayres

Mr Brough

brisk sharp

has been elbow deep in me

I imagine my intestines lilac blue

and steaming gently in the unexpected air

unravelled they can stretch

the whole way round a tennis court

they told us that in school

I never thought I’d put it to the test

the bowel reacts to being handled

can be skittish might flounce

peristalsis – that squeeze that starts as swallowing

then ripples sweet and regular right through –

must settle down into its proper rhythm

meanwhile strange surges flutter

as if a trout is netted in my belly

and now it flexes slippery and strong

I think of Mr Brough

and riverbanks

of skill honed by practice

the sly gutting of a fish

By Jan Dean

No meaning

Blurred thoughts and a head banging

with shame. A rhythmic thump

from the numbing slurs

unsteady and slumped strides

across a reflecting floor –

a cold bed, to recover from the eclipse.

My side split open from the lack

of humour. A weak link

in my pathetic body.

A grey blocked sun seeks refuge

whilst no-one is around

to hear my silence.

My vomit is unknown only to me.

Others clean the filth

of my functions.

I stir to find a head so full

of nothing, only religion

could make sense of it.

By Stephen Daniels

Shrink

Once a decade

she succeeded

in the waning.

The coiling

tighter of the spring,

the pinching of pleats.

To wake counting ribs,

protecting hipbones

from lovers,

consoling them

at the deflating

breasts.

To walk more quickly,

yet slowly now

past store windows

to admire not

la dernière mode

but la nouvelle derrière.

To stride boulevards

counting ticks, crosses:

thinner than that, fatter than that

until the day,

that sod-it day,

when rebellious child

meets feckless adult,

fails to inject

a moment’s pause

between trigger

and shot

of sugar.

The rapid unravelling,

an uncoiling spring,

the easing of seams,

the waxing.

By Sharon Larkin

previously published by Cinnamon Press in the May Day anthology, 2014, ed. Jan Fortune.

MUM AND DAD

In my mother’s kitchen was a small fridge and a derelict cooker;

already I have slipped from what I think I know

to what must be said. That cooker is long gone, its inner glass

baked brown, door hanging at an angle, looped back with wire,

to permit the accurate immolation of birds.

The lino tiles, laid with black Bostik when I was ten, have gone, too –

so have the patches from my clothes, my arms, my ears, my knees.

I used to clean that cooker. She would pay me ten bob – a horrible job,

but it suited a drive I had, to remove all corrosion, let the secrets

of the dark places be exposed – the chickens slowly crinkling in full light,

walls no longer sticky with undigested substance, food untaken,

dross, bad memories. In my mother’s kitchen were secrets. Stuck, they were,

with the Bostik under the floors, in the sticky heat of the killing oven;

invisible in the layers of my innocent skin.

In my father’s absence was a streak of distress. In his towers

of empty tobacco tins, as they accrued like debt behind cupboard doors,

was fear. When doors were opened, they crashed out – when I opened the doors.

In the pit of the stomach, the expectation of sudden noise. Of a crash,

of a scream. Of emptiness.

By Louise Larchbourne

The Forest Seamstress

My mother is making my clothes.

I hide behind a screen and trade my shoes for leaf and bark.

I tread more softly.

Brrrch, Brrrch. She feeds her material through blood and branch.

Brrrch. The birds stop to listen. I hear the rustle of skin.

A pool of leaves breathes at her feet.

Mother climbs from bark to twig. She lifts hair from my face,

lets me see. She tells me to climb. She wants the stars. I shake my head.

My mouth is packed with velvet-warm earth.

My mother laughs and rubs my skin with fresh-spun sap. I am her daughter.

She tugs my gut. I climb to please her. My intestines wind through bark and bough.

She rips satin ribbons from remnant skies and lines hidden pools; eye deep

and as watchful. I sense my soul take root.

Some days her belly growls, I run for shelter. She shakes the ground.

The sky fills with swallows’ purple light. I hide to find my way back in.

I emerge to fallen leaves. She smells of age and earth. When she dies

I become her. By winter I dress in icy armour. It keeps my heart soft.

By Jenny Hope

previously published Petrolhead, Oversteps Books, 2010

Risk!

The leaves

move too directly and with a rhythm

unmatched by the breeze.

A raggedy tab of weasel

zips the bleached and cropped pasture.

Buffered by a grey-pelted prize

worn like a moustache,

(perhaps the unfortunate shrew

obstructs its view)

it heads straight for the

astonished dog.

The lurcher begins to levitate with

tip-toed anticipation,

ears umbrella-ed

to shade the point of pounce.

He knows not to run,

not to telegraph his presence

but just as it seems

weasel and shrew are his,

the ragged bullet

ricochets off a grass blade

right from under his nose.

Now he chases! Skittered

pebbles fly in the sunshine

like drops of river water

scattered by a kingfisher

but gangle bows to rick-rack.

Hunter out-dashes hunter

snapping out of existence

at the base of an old stone wall.

In the air, hangs a pungent musk

like the scent of passion fruit

and piss.

By Mavis Moog

The Phantom Lead-swinger Strikes Again

He’s had enough

of half-job Henrys.

He doesn’t deal

in tired excuses.

If he had his way

the workers of the world

wouldn’t start the job

to begin with. He’d leave it

to the admin johnnies

in their clean collars

to churn out the paperwork,

sign the chitties, issue the requisitions,

rubber stamp and copy in triplicate,

and he’d sniff at their in-trays and invoice spikes

and slope off for a fag round the back

or a hand of cards with the apprentice lad

in some work-free corner of a disused hut,

nicely off the gaffer’s radar.

By his leave, the words

productivity and logistics

would do the decent thing

and self-erase.

Half-job Henrys

are no friends of his.

Fuck-the-job

Freddies –

they’re his

buddies.

By Neil Fulwood

All the secret things

All the children’s pictures rubbed off the board,

chalk dust too, caught in a jar.

Fairies calling from silvered plates,

the secrets of magic and every sleight of hand;

all of Houdini’s great escapes,

the wonder still intact. Take a look.

Here, every tooth the fairy mouse has paid for,

see the whole castle with its ivory bathtubs.

Imagine you lived here, you’d take tea on the lawn,

while just here, a ladybird has taken off all her spots.

She has them jittering in a box on the floor:

her bare red wings, the missing piece

of the puzzle you made and unmade again,

the invitations not sent,

the thank yous ditto,

the parties not held,

the uprising of socks unpaired.

By Natalie Shaw

Below is my Fat Choice – a poem that did not make the guest ed’s cut, but had something about it that I liked.

Yawning Stars

I watched you yawn a universe into existence

I witnessed as you sang a cosmos into style

I saw you sigh, and the heavens roared

then you smiled, and the gods came alive

I felt you move, and the stars fell into rhythm

then you danced, and the planets cycled into their place

You closed your eyes, and the full moon shined

and when they opened, the sun blazed hot

Your passion flared, and the earth shook violently

but then you laughed, and all grew calm

You said Yes, and the gates flew open

Your power coursed through every wave

You spoke the Word, and the gospel was born

Your vibration, a serenade of the holy symphony

By Scott Thomas Outlar

Amazing selection of finely honed poems. Many thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Mary – we are so glad you enjoyed them! xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just read straight through both parts of this stunning first issue – what a great selection of poems, I feel enriched for reading them, thank you!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much Rayya! This is our aim so we are so glad xxx

LikeLike

Loved all the poems but esp relevant to me, Sally Evans ‘All The Gardens’ as I prepare to move and create another, leaving behind one that has been mine for 20 years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am glad you have found a poem to make such a strong connection with xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Congratulations you’ve really started something here.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Rachael – and thank you for being part of it xx

LikeLike

Pingback: Mandy MacDonald – three poems – Clear Poetry

Pingback: Published Poetry, Bookshops and Comics – Stephen Kirk Daniels